Primary central nervous system lymphoma: treatment access and outcomes in HIV positive patients in a minority rich cohort

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is an aggressive acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) defining malignancy with poor prognosis. Historically PCNSL patients living with HIV (PLWH) had poorer outcomes compared with those without HIV, however the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has improved physicians’ capacity to prescribe chemotherapy but there is limited data on how this progress affected the outcomes of PCNSL PLWH and their ability to undergo autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) which is a potentially curative treatment (1-4). We studied the patient characteristics and outcomes for PCNSL in the Bronx, which has a high prevalence and one of the highest rates of HIV infection (about 2.5 times the national average), particularly among women and minorities (5-7). Minorities comprise 89% of the Bronx population with 29% living below the poverty line (5-7).

The main objective was to compare differences in access to ASCT in patients who had HIV versus those who did not. Multiple methotrexate (M)-based induction regimens including rituximab (R), vincristine (V), procarbazine (P), etc. have been described in literature and used clinically but there is a dearth of studies describing the benefit of addition of procarbazine to these regimens (8).

This is a single center retrospective cohort study of 53 PCNSL patients treated between 2000–2020, whose characteristics were compared by using χ2 statistics and Mann-Whitney test. Overall survival (OS) was calculated using Kaplan Meir. For analyses of socioeconomic status (SES), we used a measure of neighborhood disadvantage called the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), a composite of 17 measures validated across a range of diseases (9). High ADI indicates worse SES.

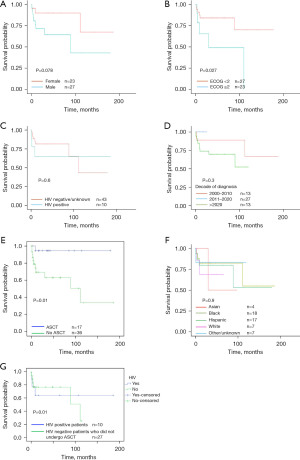

In our cohort, 19% (10/53) patients had HIV which is three times the global prevalence of HIV in patients with PCNSL (6.1%) (10). The HIV status of three patients was not available, hence they were excluded from the study. Although 32% of the patients received ASCT, they were all HIV negative. None of the patients with HIV (0/10) received ASCT. PCNSL PLWH were significantly younger than those without HIV (45 vs. 64 years, P=0.006) and were predominantly males (60% males in PLWH). Comparison of clinical characteristics of PLWH with patients without HIV is given in Table 1. Females had a better OS compared to males, a trend that was reaching statistical significance (90 months vs. not reached, P=0.07, Figure 1). Racial/ethnic distribution of our population was as follows: Asian (7%), Black (34%), Hispanic (32%), White (13%), and other/unknown (13%). Our population had a higher poverty index than the national average [median New York (NY) state ADI 5th percentile, range 1–10, standard deviation 1.5]. Most common induction regimens were rituximab methotrexate vincristine (RMV) (47%) followed by rituximab methotrexate procarbazine vincristine (RMPV) (23%).

Table 1

| Demographics | †HIV positive (n=10) | HIV negative (n=40) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.006* | ||

| <30 | 2 | 0 | |

| 30–60 | 7 | 14 | |

| >60 | 1 | 26 | |

| Sex | 0.736 | ||

| Male | 6 | 21 | |

| Female | 4 | 19 | |

| Race | 0.478 | ||

| White | 0 | 7 | |

| Black | 4 | 14 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 12 | |

| Asian | 0 | 3 | |

| Other | 1 | 4 | |

| ECOG at diagnosis | 0.574 | ||

| 0 | 2 | 5 | |

| 1 | 2 | 18 | |

| 2 | 2 | 9 | |

| 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| 4 | 3 | 4 | |

| Karnofsky at diagnosis | 0.53 | ||

| ≥90 | 5 | 17 | |

| <90 | 5 | 23 | |

| ECOG after treatment | 0.369 | ||

| 0 | 2 | 8 | |

| 1 | 3 | 9 | |

| 2 | 0 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 10 | |

| 4 | 5 | 10 | |

| Karnofsky post treatment | 0.901 | ||

| ≥90 | 5 | 13 | |

| <90 | 5 | 27 | |

| ASCT for consolidation | 0.01* | ||

| Received | 0 | 17 | |

| Not received | 10 | 23 | |

| WBRT for consolidation | 0.405 | ||

| Received | 4 | 7 | |

| Not received | 6 | 33 | |

| Best response | 0.544 | ||

| CR | 3 | 23 | |

| PD | 5 | 7 | |

| PR | 1 | 5 | |

| SD | 1 | 5 | |

| Survival probability | 0.538 | ||

| Overall, 1-year survival | 63% | 82% | |

| Median OS | Not reached | 111 months | |

| Early mortality (within 3 months of PCNSL diagnosis) | 20% | 10% | 0.6 |

| Reasons for not receiving ASCT | (I) Poor performance status (60%); (II) refused ASCT (20%); (III) different consolidation therapy chosen in view of poor compliance to prior oncological treatment (20%) | (I) Poor performance status (31.9%); (II) refused ASCT (12.8%); (III) different consolidation therapy chosen in view of poor compliance to prior oncological treatment (15.9%); (IV) unknown (27.7%); (V) decline in functional status after induction therapy (6.4%); (VI) lost to follow up (5.3%) | – |

†, the HIV status of three patients could not be found, hence they have not been described in the table above; *, statistical significance. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; WBRT, whole brain radiotherapy; CR, complete response; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; OS, overall survival; PCNSL, primary central nervous system lymphoma.

Patients who received consolidative ASCT had significantly better OS than those receiving other consolidation regimens (mean OS 170 vs. 128 months, P=0.01 and median OS not reached compared with 80 months, Figure 1E). All patients receiving ASCT were HIV negative. There was no difference between one year OS between ASCT and whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) (87% vs. 76%, P=0.08). Adding procarbazine to induction regimens did not improve OS (median OS 147 vs. 122 months, P=0.23). The survival rate in those who underwent ASCT was remarkable, with 87.5% alive at the time of last visit (range time from transplant: 161 to 2 months, median OS after ASCT 30 months). Race/ethnicity, age and SES did not affect access to ASCT or OS. PLWH were significantly less likely to receive not only ASCT (P=0.01) but any induction treatment (60% vs. 95%, P=0.01). There is no difference in receiving induction WBRT in two groups (OR =9, P=0.09) than those without HIV. All HIV negative patients received treatment but 20% of PLWH did not receive any treatment. We evaluated why PLWH were not deemed to be suitable candidates for transplant and found that all the patients with uncontrolled HIV (60%, 6/10) (CD4 T cell count <200 cells/microlitre and HIV RNA >500 copies/mL) did not get ASCT due to poor performance status. Four PLWH with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0–1 after induction treatment and controlled HIV did not receive ASCT due to refusal (reasons like religious/personal beliefs in 2/4) and treating provider’s recommendation for WBRT given poor compliance to prior oncological treatment (2/4, Table 1). PLWH did not have a significantly different ORR (70% vs. 40%, P=0.5) and 1-year OS (65.5% vs. 80%, P=0.5) than their HIV negative counterparts. Comparable survival outcomes in PCNSL patients with and without HIV are described in literature and are likely multifactorial but may be explained by the fact that 90% of PLWH were receiving HAART which has alone shown to lead to long-term remission and improved outcomes (1,11). The benefits of consolidative ASCT for PLWH could not be addressed in this study as no PLWH underwent ASCT [for detailed information, see the Supplementary file (Appendix 1)].

To conclude, ASCT improved survival in PCNSL but HIV positive status limited the utilization of ASCT, mainly due to poor functional status. Despite the cohort being socioeconomically disadvantaged and with potential barriers to treatment, the survival outcomes were pretty impressive with 70% (7/10) of the PLWH and 81.4% (35/43) of the HIV-negative/unknown patients alive at the last follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study describing the disparities in utilization of ASCT in PCNSL PLWH. Early treatment with improved HAART and expanding access to multidisciplinary healthcare will enhance functional status and utilization of ASCT in PLWH. Limitations to our study include a retrospective design, small sample size, minority rich cohort which may not be generalizable and a single-center experience.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Stem Cell Investigation. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://sci.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/sci-2023-021/coif). AV serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Stem Cell Investigation. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Diamond C, Taylor TH, Aboumrad T, et al. Changes in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: incidence, presentation, treatment, and survival. Cancer 2006;106:128-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bojic M, Berghoff AS, Troch M, et al. Haematopoietic stem cell transplantation for treatment of primary CNS lymphoma: single-centre experience and literature review. Eur J Haematol 2015;95:75-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Illerhaus G, Marks R, Ihorst G, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem-cell transplantation and hyperfractionated radiotherapy as first-line treatment of primary CNS lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3865-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Colombat P, Lemevel A, Bertrand P, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation as first-line therapy for primary CNS lymphoma in patients younger than 60 years: a multicenter phase II study of the GOELAMS group. Bone Marrow Transplant 2006;38:417-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Women and HIV in the United States. Available online: https://www.kff.org/hivaids/fact-sheet/women-and-hivaids-in-the-united-states/

, accessed March 9, 2020 -

Atlas Plus-Maps -

CDC - Löw S, Han CH, Batchelor TT. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2018;11:1756286418793562. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kind AJH, Buckingham WR. Making Neighborhood-Disadvantage Metrics Accessible - The Neighborhood Atlas. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2456-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Franca RA, Travaglino A, Varricchio S, et al. HIV prevalence in primary central nervous system lymphoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathol Res Pract 2020;216:153192. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barta SK, Samuel MS, Xue X, et al. Changes in the influence of lymphoma- and HIV-specific factors on outcomes in AIDS-related non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ann Oncol 2015;26:958-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Narvel H, Vegivinti C, Vikash S, Bazarbachi AH, Pradhan K, Wang S, Hammami MB, Narvel N, Yakkali S, Ansari S, Nabi AG, Mohammed T, Mantzaris I, Konopleva M, Goldfinger M, Gritsman K, Cooper D, Shastri A, Shah N, Kornblum N, Verma A, Sica RA. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: treatment access and outcomes in HIV positive patients in a minority rich cohort. Stem Cell Investig 2023;10:17.